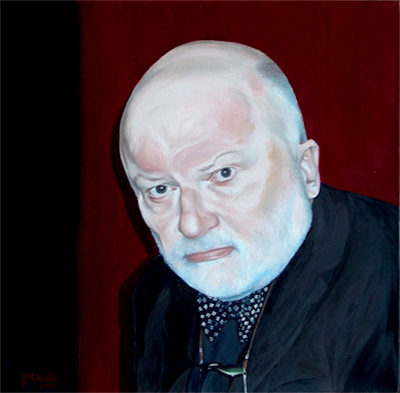

Oil on Canvas, 2007, 50cm x 50cm

Purchased by Emmanuel College, Cambridge

I had published in Stand a sequence of sonnets called ‘Portrait of the Poet as a Young Dog’. Two of them concerned Hill. They derived from an unhappy passage in my life that saw me spend a year at Leeds University where I did no appropriate work, attended few lectures, and almost no tutorials. It is hard to think how I got away with it for as long as I did. I was only interested in trying to write poems. But two things I did do. I attended two courses of lectures very assiduously, one, a series on aesthetics by Quentin Bell, the other by Hill on poetry from W. B. Yeats to Ted Hughes and Thom Gunn. Hill’s course has become legendary among a subsequent school of Leeds poets, chief among them Jon Glover and Jeffrey Wainwright, graduate students, in my short time there.

So Welsh wilderness-green and wildly shy was I in those days, I wouldn’t say boo to a goose, not even to those two gentle souls. Nothing would have induced me to buttonhole Hill. But I sat in the very front of the lecture theatre and observed him closely. (I could see the beads of sweat on his forehead.) He was I thought wonderfully gloomy, and at times engagingly savage, in his literary criticism (he mauled Thom Gunn with unforgettable brutality), and towards the supposed poetic aspirations of some in his audience. To my mind, fresh out of Wales, he had something of Dylan Thomas about him that surely helped me take to him. I could see (and approve) it very obviously in his early ‘Keble’ sequence ‘Genesis’. He read with a Thomasian sonority and not in the flattened matter-of-fact, uninflected manner of the so-called Movement poets. I have always tended to prefer that.

According to Hill, I caught his likeness at that time, ‘uncannily’ – ‘sweating in his funeral suit of charcoal grey’:

His black shirt, in that artificial light,

caught tenebrous hues, green as Baudelaire

’s dyed hair; his pudgy face so queer,

his brow so damp, as if he spent the night

in hell-on-earth, every day of the year,

and knew he was the only poet there.

It was momentous for me to meet him at last. I did so at Christ Church, Oxford, in Peter McDonald’s rooms. A devoted reader of his work for decades by then, I was awestruck and pretty well tongue-tied before him, no matter he was extremely benign and twinkly-eyed towards me. For his part, Geoffrey could always be difficult to stir into conversation, at the best of times. Though once launched he was invariably magnificent and often Hill-arious. I can’t remember a word that was said on that first occasion but arrangements were made. There would be a publication, a pamphlet. Peter McDonald oversaw an arrangement with the Christopher Tower Trust whereby funds were to be used to further poetry’s cause. So for the first and only time Clutag received a significant grant which comfortably enabled several pamphlet publications including what became Hill’s A Treatise of Civil Power (2005).

This was perhaps in spring of 2004. I was working at Oxford University Press by then. On 29 September that year I received an email from Ken Haynes (Geoffrey’s close friend, amanuensis and editor) with seven attachments. Six poems and a mock-up of the title page, giving the precise typography and design required, to approximate to, but not to reproduce as facsimile, Milton’s pamphlet of the same name, down to the place of publication:

The poems were set and proofs made ready. But progress was delayed by the addition first of one poem and then another. These were sent in a most apologetic manner. I was at liberty to turn them down. I wasn’t so foolish and what began as a pamphlet expanded, not unalarmingly, in terms of binding, into what Geoffrey called a ‘booklet’. It was a brilliant new start for Clutag Press which up to that point had trafficked only in small two-page leaflets, hand-set on an Arab printing press. (I should say that the version of the title poem in the booklet’s pages is to be found nowhere else and is in my view far superior to the one subsequently published in the book of the same name.)

As you will know from the website Clutag Press went on to publish two books by Geoffrey Hill and to issue a CD of a reading he gave in Oxford’s Sheldonian Theatre. I would sign up his critical writings for OUP, and also his collected poems. In that time I got to see Geoffrey regularly, in Boston, Oxford, and latterly in Cambridge, and enjoyed his great warmth, extraordinary kindness, and personal concern (for my and my family’s well-being). He was deeply proud to be a copper’s son from Bromsgrove and that was a starting place at which it was most comfortable, and often most illuminating, to meet him. He was an intellectual giant but the artist in him held a simple ground too. I saw this very clearly once when, on the morning after his Sheldonian reading, 2 February 2006, I drove him to Kidderminster where his wife Alice Goodman was then living, serving as an Anglican chaplain there.

I slowly realised as we travelled farther and farther from Oxford and nearer and nearer our destination that we were on a nostalgia journey, into the realms of Goldengrove, into Offa’s territory, and the nearer it we got so he became more and more animated. He seemed to radiate sensual pleasure. At one point, as we passed on the other side of the road, a great black steam engine on the back of a low-loader, I thought Geoffrey was going to jump through the roof of the car at the sight of it. He was like a child in his excitement. Here was the past made manifest, here was childhood, here was the Eden of the West Midlands in transit, here was memory redeemed in the moment. We had to take particular roads. I had especially to see the sand quarry in which the young Offa – after flaying Ceolred – ‘journeyed for hours, calm and alone, in his private derelict sandlorry named Albion’. This was the territory of ‘The Jumping Boy’, who is celebrated so marvellously in Without Title (2006), then newly published.

I have far too much to relate about him than is appropriate here and now. The fact of his death – though I had heard he was ill – came as such facts do as a shock of numbing force. He was a literary giant, a staggeringly learned man. That I of all people should ever have known him and been numbered among his friends still seems as incredible to me as it would have done to my youthful, delinquent self at Leeds in 1965.

3rd July 2016